Collecting Consciousness

May 2013

© Adam Granger

I often ask people if they collect anything. At first they say no, but then, upon reflection, they say, “Well, I do collect ____”, and you can fill in the blank with pretty much any noun you can imagine. Last week, a cashier at a thrift store told me she collects owls.

I collect small things, maybe miniature, but not necessarily. The two criteria are that they've got to be small and I've got to think they're neat. I've had this passion as long as I can remember. I still have items from my early childhood: a tiny black pot, a small leather dictionary, a miniature deck of playing cards and twenty or so china animals (an unsettling synchronicity between myself and the pathetic Laura Wingfield, the owner of Tennessee Williams' titular glass menagerie).

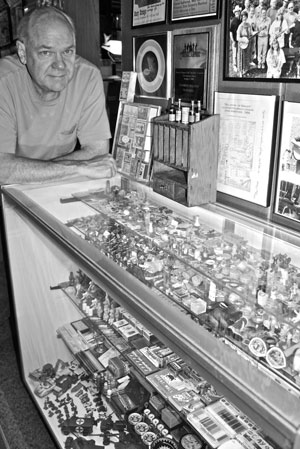

My adult collecting started in earnest about 25 years ago, when we bought our house and I suddenly had space not hitherto afforded by apartments and car trunks. I acquired a large commercial glass display case and filled it with literally a thousand cool little things. It lived in our dining room for awhile, but when I got a second, bigger case and filled it, too, it became clear even to me that the collection needed to migrate southward.

Today, my basement “museum” contains dozens of display cases and boxes holding tens of thousands of items in sixty-odd collections: miniature versions of knives, books, slot machines (over 200!), harmonicas, tools and puzzles, as well as folding fans, wind-up toys, styrene figures, travel sewing kits, money facsimiles, boxes of staples, cloth patches, sets of nesting boxes, campaign buttons, and—well you get the picture. All that's missing is a partridge in a pear tree.

Am I, then, like Miss Wingfield, communing more with her menagerie than with the outside world? Well, I certainly was as a child. Williams may as well have been sitting in my house with a pad and pencil, watching the eleven-year-old Adam acquiring his pets week by week, allowance by allowance. But what about now? Am I still like Laura? I think not; I rarely feel like her anymore.

A friend of mine, William Davies King, a drama professor in Santa Barbara, has written a wonderful hemi-autobiography called Collections of Nothing. He is more the philosopher than I, and a terrific writer. Whereas I describe “a collection” as “a deliberately accumulated and curated group of three or more similar things,” his definition is “a multiplicity of objects explainable only by the fact that in relation to each other they define a unity.” Both definitions end at the same place, and my route is faster, but his is more scenic.

As to the Glass Menagerie Syndrome, King believes that the impulse to collect comes from wounds in our personal lives, a theory to which I also subscribe. (My wife once remarked that I didn't have enough as a kid. “Of what?” I asked her. “Of anything,” she replied.)

But wait: I'm happy, now, and well-adjusted (at least in the ways that count), and yet I love collecting more than ever. What's up with that? While my collecting may or may not still be delivering a steady IV drip to whatever old wounds I bear, the lion's share seems to be paid toward the sheer, non-neurotic pleasure and satisfaction of seeing sets of things lined up neatly in well-lit display cases.

As for acquisitions, people give them to me, or I find them on the ground, or at thrift stores, or on Ebay. Nothing costs much; these things are of little value. Nobody else wants the stuff I want, which makes me different from the collector of Impressionist art or Stickley furniture.

But I am also different from King, who, as his book title suggests, collects things of no value—to use his words, “a super-superfluity of sub-substance.” He gave a paper recently in Washington DC for the Popular Culture Association which he illustrated with Powerpoint images of his collection of 84 different Life Cereal boxes. In total, he has over two thousand cereal boxes. And pressed into scores of ring binders are tuna can labels, water bottle labels, “tamper-evident” seals, 181 linings from security envelopes, and dozens of other worthless collections.

Except that they're not worthless (and you knew I was going to say that). Today's prosaic irrelevancy is tomorrow's archeological rock star. And worth can be made from worthless: my mom used to collect pieces of wire that she found in the street. She'd hang them on our walls, and they'd get lots of compliments. Thus did the valueless became the valued, and if King's labels and boxes survive his life, they will be gold to future social scientists and armchair time-travelers. I can't imagine that the Smithsonian won't jump at the chance to acquire his oeuvre.

And what of my collections? Well, probably not Smithsoniable, but there is money there, if my progeny has the patience to ferret it out. (Reverse Ebay engines!)

And if they don't, watch the dumpster behind our house after you've read my obit; there'll be some good stuff in there.

I collect small things, maybe miniature, but not necessarily. The two criteria are that they've got to be small and I've got to think they're neat. I've had this passion as long as I can remember. I still have items from my early childhood: a tiny black pot, a small leather dictionary, a miniature deck of playing cards and twenty or so china animals (an unsettling synchronicity between myself and the pathetic Laura Wingfield, the owner of Tennessee Williams' titular glass menagerie).

My adult collecting started in earnest about 25 years ago, when we bought our house and I suddenly had space not hitherto afforded by apartments and car trunks. I acquired a large commercial glass display case and filled it with literally a thousand cool little things. It lived in our dining room for awhile, but when I got a second, bigger case and filled it, too, it became clear even to me that the collection needed to migrate southward.

Today, my basement “museum” contains dozens of display cases and boxes holding tens of thousands of items in sixty-odd collections: miniature versions of knives, books, slot machines (over 200!), harmonicas, tools and puzzles, as well as folding fans, wind-up toys, styrene figures, travel sewing kits, money facsimiles, boxes of staples, cloth patches, sets of nesting boxes, campaign buttons, and—well you get the picture. All that's missing is a partridge in a pear tree.

Am I, then, like Miss Wingfield, communing more with her menagerie than with the outside world? Well, I certainly was as a child. Williams may as well have been sitting in my house with a pad and pencil, watching the eleven-year-old Adam acquiring his pets week by week, allowance by allowance. But what about now? Am I still like Laura? I think not; I rarely feel like her anymore.

A friend of mine, William Davies King, a drama professor in Santa Barbara, has written a wonderful hemi-autobiography called Collections of Nothing. He is more the philosopher than I, and a terrific writer. Whereas I describe “a collection” as “a deliberately accumulated and curated group of three or more similar things,” his definition is “a multiplicity of objects explainable only by the fact that in relation to each other they define a unity.” Both definitions end at the same place, and my route is faster, but his is more scenic.

As to the Glass Menagerie Syndrome, King believes that the impulse to collect comes from wounds in our personal lives, a theory to which I also subscribe. (My wife once remarked that I didn't have enough as a kid. “Of what?” I asked her. “Of anything,” she replied.)

But wait: I'm happy, now, and well-adjusted (at least in the ways that count), and yet I love collecting more than ever. What's up with that? While my collecting may or may not still be delivering a steady IV drip to whatever old wounds I bear, the lion's share seems to be paid toward the sheer, non-neurotic pleasure and satisfaction of seeing sets of things lined up neatly in well-lit display cases.

As for acquisitions, people give them to me, or I find them on the ground, or at thrift stores, or on Ebay. Nothing costs much; these things are of little value. Nobody else wants the stuff I want, which makes me different from the collector of Impressionist art or Stickley furniture.

But I am also different from King, who, as his book title suggests, collects things of no value—to use his words, “a super-superfluity of sub-substance.” He gave a paper recently in Washington DC for the Popular Culture Association which he illustrated with Powerpoint images of his collection of 84 different Life Cereal boxes. In total, he has over two thousand cereal boxes. And pressed into scores of ring binders are tuna can labels, water bottle labels, “tamper-evident” seals, 181 linings from security envelopes, and dozens of other worthless collections.

Except that they're not worthless (and you knew I was going to say that). Today's prosaic irrelevancy is tomorrow's archeological rock star. And worth can be made from worthless: my mom used to collect pieces of wire that she found in the street. She'd hang them on our walls, and they'd get lots of compliments. Thus did the valueless became the valued, and if King's labels and boxes survive his life, they will be gold to future social scientists and armchair time-travelers. I can't imagine that the Smithsonian won't jump at the chance to acquire his oeuvre.

And what of my collections? Well, probably not Smithsoniable, but there is money there, if my progeny has the patience to ferret it out. (Reverse Ebay engines!)

And if they don't, watch the dumpster behind our house after you've read my obit; there'll be some good stuff in there.

|

To see some of Adam's collections,

click on the button at right |